Introduction

One of the most powerful empires in history, Persia, nowadays Iran has been at the forefront of regional, political, economic and cultural developments in the wider area of the Middle East and the Persian Gulf regions. After the Iranian Revolution in 1979, Tehran gradually adopted a new model of foreign policy that directly opposed the interests of western powers in the area, by enhancing its presence and influence in neighbouring countries. In this context, Iran’s nuclear program that started advancing after the dawn of the new millenia, posed numerous questions concerning national security issues of its adversaries like Saudi Arabia and the rest of the countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council and even Israel. Simultaneously, the United States saw a direct threat to its core strategic interests in the area, as Iran continues to constitute one of the U.S.’s key threats to its national security.

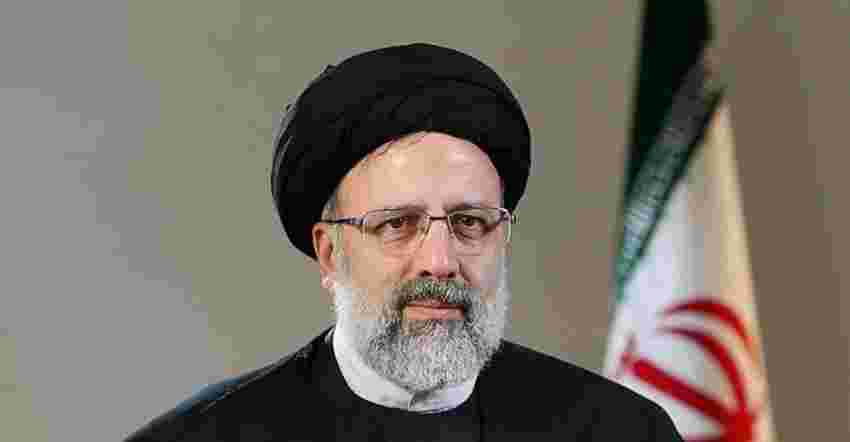

The breakthrough that was achieved in Vienna in 2015 with the signature of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and the P5+1 Group did not prosper as the U.S. under President Donald J. Trump withdrew in 2018 for violations of the treaty by Iran. However, today, as Iran prepares to hand over power to its new conservative president Ebrahim Raisi there is a widespread concern about Tehran’s nuclear program and how it could affect the balance of power in the Middle East but also on a global scale.

Ergo, as western powers express an augmenting concern about the need for the restart of the JCPOA talks, this report aims to analyze and explain Iran’s complex relations with different countries of the region and outside of it as well as to recommend possible measures that could not only prevent a possible escalation of tension but also to ameliorate the relations between Tehran and the West. Henceforth, the first part will provide the essential historical framework of Iran’s efforts to experiment and develop nuclear capacities. This part demonstrates that the Iranian nuclear program is connected with the wider Iranian foreign policy objective to augment its military capacities and to enhance its influence abroad and to legitimize the regime inside the country. The second chapter examines the turbulent relations between Tehran and the nowadays weakened regional hegemon the United States. The tense bilateral relations between the two nations after 1979 have been a key factor that pushed Tehran to develop its nuclear program to achieve nuclear deterrence. In this context, the U.S.’s withdrawal from Afghanistan is also portrayed in this report to provide a wider picture of the radical power shift that occurs in the Middle East today. Moreover, the study also pictures Iran’s efforts to influence the politics of its neighbours focusing on Syria and Iraq. Concluding the final chapter provides a list of possible future scenarios and recommendations in case of a successful development of nuclear military capacities by Tehran.

Historical context

The interest of Iran in developing nuclear technology dates back to the 1950s with the inclusion of the country in the “Atoms for Peace” Programme [1], which was carried out by the United States. Despite the suspension of the US assistance following the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the Iranian government remained interested in nuclear technology. As a result, an intensive nuclear fuel cycle took place, becoming the subject of international negotiations and sanctions between 2002 and 2015. In July 2015, the negotiations between the P5+1 and Iran ended with the adoption of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), according to which Iran was committed to limit its nuclear capacity in return for a sanctions relief. However the announcement of US President Donald Trump to unilaterally exit the agreement and impose sanctions on Iran in May 2018 provoked the crisis of the JCPOA, leading Iran to stop complying with the limitations imposed by the agreement.

Under the “Atoms for Peace” Programme, the United States provided the Tehran Nuclear Research Center (TNRC) with a 5MWt research reactor (TRR), fueled by highly enriched uranium (HEU). In exchange for US cooperation, Iran signed the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons Treaty (NPT) in 1968 and a Safeguards Agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 1974, according to which all the Iranian nuclear facilities were subjected to IAEA inspection. The installation of the reactor in 1967 represents the starting point for the development of several ambitious nuclear programmes carried out during the 1970s. In 1973, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi charged the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) to produce 23,000MWe of nuclear power by the end of the century (Burr, 2009). In order to achieve this ambitious goal, Iran concluded several nuclear technology related contracts with foreign suppliers and invested in education and training for its staff (Reardon, 2012), which will provide the country with an impressive capability in nuclear technologies by the beginning of the Revolution in 1979 (Nuclear Threat Initiative, 2020).

The opposition of the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to nuclear technology and the migration of nuclear experts caused the temporary suspension of the national nuclear programme (Malus, 2018). However, in 1984 Khomeini expressed a renewed interest in nuclear power, seeking the assistance of international partners to complete the construction of the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant (Ishaque, Shah, Ullah, 2017). The war with Iraq (1980-1988) dealt a setback to the programme because of the consumption of strategic resources and the damage of the existing nuclear power implants. By the end of the war, the Iranian government decided to refocus on nuclear technology acquisition (Reardon, 2012), signing long-term nuclear cooperation agreements with Pakistan in 1987 and with China in 1990, and obtaining the Russia commitment to complete the construction of the Bushehr reaction and to build three additional reactors in 1995 [2] (Smith and Dobbs, 1995). In the meantime, the US belief that the Iranian civilian nuclear programme was used to cover clandestine nuclear weapons development brought the US government to pressure potential suppliers to limit their cooperation with Iran (Burr, 2009). The political and diplomatic initiative exercised by the US President Ronald Reagan achieved to reduce the cooperation from international suppliers, forcing indeed China to not supply Iran with the research reactor and the two Qinshan power reactors, blocking Argentina from concluding the agreement for uranium enrichment and heavy water production facilities, and pushing Russia to not deliver the uranium enrichment plant. However, looking at the practical level, several institutes and entities from Russia and China, together with the substantial assistance provided by the A.Q. Khan network, continued to support Iranian engineers in the development of the nuclear programme (Malus, 2018). The cooperation with Pakistan was crucial to achieve the success of the Iranian programme and provided the basis for producing highly enriched uranium (HEU) – which constitutes a fundamental element to fuel a weapon.

In 2002, the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) revealed the existence of secret nuclear facilities in Iran, including the Natanz Enrichment Complex and a heavy water production plant at Arak, later confirmed by Iran to the IAEA Director in 2003. To avoid a referral to the UN Security Council, as proposed immediately by the US, Iran entered into negotiations with the EU-3 (France, United Kingdom, and Germany), which were concluded by the signing of the Paris Agreement. According to it, Iran committed not only to sign the Additional Protocol to the NPT, requiring expanding safeguards measures and inspection carried out by IAEA, but it also agreed to suspend the activities for the enrichment of uranium during the negotiations and to work with the EU-3 countries to find a mutually beneficial long-term diplomatic solution. On the other hand, the EU-3 agreed to assist Iran with civil nuclear technology and reduce the economic sanctions. The negotiations remained stuck on the issue related to the suspension of the uranium enrichment activities, since the EU-3 countries required its definitive interruption while Iran argued its right to an enrichment program for a peaceful use (Reuters, 2005). The impossibility to reach an agreement on this matter and the approaching of the presidential elections brought Teheran to notify the IAEA to resume its uranium conversion activities at Isfahan in 2005 (Reardon, 2012). The IAEA Board of Governors adopted a resolution denouncing Iran non-compliance with its Safeguards Agreements, while the President George W. Bush signed the Executive Order No. 13382, blocking the financial assets of individuals and entities supporting WMD proliferation (Executive Order, 2005).

At the beginning of 2006, Iran ended its voluntary implementation of the Additional Protocol and resumed enrichment at Natanz. The consequent request of the IAEA Board of Governors to report the case of Iran by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) met the opposition of Russia and China to adopt sanctions. Because of the impasse at the UNSC level, the other four permanent members of the Security Council plus Germany (P5+1) offered a package of positive inducements to Iran in exchange for the suspension of enrichment activities as a precondition for any negotiations. The failure of this new attempt convinced the UNSC to approve the Resolution No. 1969 demanding the suspension of the enrichment activities, banning the international transfer of nuclear and missile technologies to Iran, and warning Iran that its failure to comply could result in punitive Security Council measures, such as economic sanctions (Kerr, 2006). Because of Iran’s non-compliance, the Security Council adopted a new resolution (No. 1737) in December 2006 obligating Iran to suspend the work on its heavy-water reactors and ratify the IAEA’s Additional Protocol. As warned in the previous Resolution, sanctions were imposed against both Iran and Iranian individuals and entities deemed to be providing support to Iran’s proliferation related activities (UNSCR 1737, 2006). Regardless of the dramatic impact of these sanctions, President Ahmadinejad vowed to ignore Resolution 1737, continuing to operate and expand the Natanz enrichment facility. Thus, UNSC unanimously adopted Resolution 1747 which extended the financial sanctions to more Iranian entities and banned Iranian arms exports (UNSCR 1747, 2007), while again Tehran responded with further restrictions on inspections and safeguards. In 2007, the EU and Iran opened a round of talks to achieve an agreement based on a “freeze-for-freeze” situation, in which the UNSC would cease deliberations over further sanctions in exchange for a commitment of Iran not to further expand its enrichment program. However, this proposal was rejected by both the Bush administration and President Ahmadinejad (Reardon, 2012). The impossibility to reach an agreement and the information collecting by the US intelligence about Iran’s progress on its nuclear program pushed the UNSC to approve Resolution 1803, which expanded the list of individuals and entities subject to frozen funds, financial assets and economic resources and required states to “prevent the entry into or transit through their territories” of individuals involved in the Iranian nuclear programme (UNSCR 1803, 2008). As for the previous sanctions, also these ones were far short of what the US had proposed. In June 2008, the P5+1 presented a new comprehensive proposal, which included the previous incentives offered in 2006 and economic incentives, access to LWR technology, and a guaranteed nuclear fuel supply. Again the request of the P5+1 regarded the freezing of any Iran’s expansion of its enrichment activities. Regardless of the willingness of the US to send its representative, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei reiterated its insistence in continuing with nuclear development (Cowell, 2008). The UNSC responded by adopting Resolution 1835 in September 2008, simply reaffirming the four previous resolutions and the commitment of the Security Council to a negotiated solution to the Iranian nuclear issue.

The election of Barack Obama as a US president was followed by a review of the policy towards Iran. Indeed, the newly-elected US administration expressed immediately its commitment to achieve a diplomatic compromise and to directly participate in all P5+1 negotiations. However, despite a “professed greater willingness to negotiate” (Reardon, 2012), some elements of the previous administration’s approach were maintained while the military option was never put off the table. The announcement of Iran of the acquisition of the entire nuclear fuel cycle and the hardening of Israel’s position towards Iran following the election of Benjamin Netanyahu (Stolberg, 2009), pushed the US to increase the pressure over Teheran and present in Geneva a “fuel-swap” proposal in 2009, according to which basically Iran would be given the necessary fuel, but only after most of its own stocks of enriched uranium had been exported out of the country. The idea behind this proposal was to buy time for the negotiations to make progress, since it did not resolve the main dispute related to the enrichment activities. After the initial approval of this fuel-swap arrangement by the representatives from the P5+1 and Iran in October 2009, the political resistance in Tehran from all sides pushed President Ahmadinejad to reject the deal, presenting instead a counter-proposal – which was immediately dismissed by the IAEA and the United States as inconsistent with earlier negotiations. Tensions with the international community further increased with the renewed focus of the P5+1 on sanctions and the defiance of Iran as a response. In June 2010, the UN Security Council approved another set of sanctions under the Resolution No. 1929, however without being able to directly affect the Iranian oil and gas sector because of the block imposed by China and Russia to the adoption of these kinds of measures. The Resolution banned Iran from investing in nuclear and missile technology abroad, established a complete arms embargo, prohibited Iran from undertaking any activity related to ballistic missiles and, moreover, it included financial sanctions targeting the ability of the country to finance proliferation activities.

After the breakdown of the fuel-swap agreement, the P5+1 were not able to achieve any positive results in the talks with Iran, also because Teheran insisted on the suspension of all the economic sanctions as a precondition to open again any negotiation (Erlanger, 2011). On 17 May 2010, Brazil, Turkey and Iran issued a joint statement attempting to resuscitate the fuel-swap proposal, which however was rejected by Western countries (Ishaque, Shah, Ullah, 2017). The tension between the West and Iran increased dramatically in 2011 after the release by the IAEA of a very detailed report on a secret nuclear weapons program carried out by Iran in the past. Although basically all the information in the report had been known previously, the IAEA presented for the first time the possible military dimension of the nuclear program. Despite the relevance of the information contained in the report, China and Russia opposed the adoption of new sanctions against Iran, while the US and the European Union launched a series of unprecedented unilateral measures (BBC News, 2012), provoking an escalatory response of Iran, such as with the expulsion of British diplomats from the Embassy of Tehran. For the first time, the US designated the Government of Iran and all Iranian financial institutions as entities of money laundering concern, warning financial institutions around the world that doing business with Iranian banks entailed significant risks. During the spring of 2012, several rounds of talks took place between Iran and the P5+1, with both parties agreeing on the necessity to take substantive actions. However, despite the numerous attempts to reach a compromise, the sides continued to remain far apart, provoking the suspension of these high-level talks (Ishaque, Shah, Ullah, 2017).

The victory of Hassan Rouhani at the presidential election in June 2013 represents a turning point in the progress of the international talks about the Iranian nuclear program. Indeed, despite the reaffirmation of the importance for Iran to maintain its nuclear program, the newly-elected president immediately called for the resumption of the negotiations with the P5+1. Thus, in October 2013, a first round of talks took place in Geneva, which was followed by two additional rounds of intensive negotiations. On November 24th, Iran and the P5+1 announced the reaching of an agreement on a Joint Plan of Action (JPOA), while the IAEA and Iran agreed on a Framework for Cooperation (FFC) where both parties expressed their willingness to cooperate further “with respect to verification activities to be undertaken by the IAEA to resolve all present and past issues” (IAEA, 2013). In January 2014, the implementation of the Joint Plan of Action began, while the US and the EU assured their commitment to waive the sanctions outlined in the deal. During all the year, the negotiations will positively continue, indicating the possibility to finally reach a deal to resolve the Iranian nuclear program issue.

On 14 July 2015 the P5+1 States and Iran signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), while a few days after the UN Security Council adopted the Resolution 2231 endorsing the nuclear deal and the lifting of the sanctions once key steps were taken according to the deal. The JCPOA is designed to limit Iran’s “breakout time” to a nuclear weapon from an estimated few months to one year or more and in this way give the international community the necessary time to respond. This is possible because the deal required the implementation of several measures aimed at limiting Iran’s ability to enrich uranium. Following the introduction of the JCPOA, the IAEA had guaranteed Iran’s implementation of the deal through quarterly verification and monitoring reports in accordance with the Resolution 2231.

Since the introduction of the Iran Nuclear Agreement Review Act of 2015, the US administration has always had to be accountable to the US Congress. According to this act, indeed, the President is required to certify the compliance of Iran with the deal to Congress every 90 days. With the election of President Donald Trump, these periodic reviews became an opportunity for criticizing directly the compliance of Iran with the deal. On 13 October 2017, President Trump announced that his administration would no longer certify Iran’s compliance with the JCPOA on the basis of Iranian technical violations of the deal – without however withdrawing the US from the agreement (NPR, 2017). Few months later, the authorization of President Trump to the U.S. Congress to re-impose nuclear sanctions against Iran was not followed by the adoption of any concrete measure. In April 2018, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shared a report revealing detailed information recollected by the Israeli intelligence on the Iranian pursuing of a nuclear weapons program (Holmes and Borger, 2018). The reaction of the international expert community was dismissive and it accused the Israeli report of trying to persuade Washington to withdraw from the JCPOA (Pollack, 2018). Indeed, in May 2018, President Trump announced the redrawing of the US from the agreement and the reimposition of sanctions against Iran (Ladler, 2018). Without referring to a specific violation committed by Iran, President Trump accused Iran of supporting terrorism and the pursuit of balistic missiles (New York Times, 2018). The EU3 responded with a joint statement expressing their willingness to continue supporting the deal and the establishment of a non proliferation regime, while the UN and several actors of the international community expressed clearly their concerns about the decision of the Trump administration. However, in response to the re-introduction of the US sanctions, Iran reduced its compliance with JCPOA, however continuing to cooperate with IAEA relatively to some sites.

Iran-GCC Countries

The Middle East has recently been a particularly newsworthy region of the globe for the various political tensions that have occurred among the members of this region, which include events like the war raging in Syria, the war in Yemen, the unravelling of the Iran nuclear agreement, which was signed in 2015 and even the Qatar crisis. There is one political actor, which has been involved in each and every one of these events, and that is Iran, which has been progressively increasing its activities in the region, notably since 2012 and its intervention in the Syrian civil war, which has resulted in its neighbours in the Gulf watching Iranian actions with increasing weariness and it is a common fear that was has been detailed as Iran’s “regional hegemonic ambitions” would directly and indirectly affect them (Vakil, 2018; Itayim, 2021). This feeling can also be exacerbated depending on the actions taken by the United States, which several of the Gulf countries see as their main protector, this was particularly the case under the administration of President Barack Obama, as several of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries believed that this US administration increased its focus on Iran and signing the nuclear agreement. Thus, it has been widely argued among these countries that these actions taken by the US emboldened Iran and this has resulted in Iran carrying out actions, which have severely destabilised the region, for instance supporting Bashar al-Assad in Syria, the Houthis in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon or the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) in Iraq. Not only that, but it has also been reported that Iran has been trying to exert their influence for inciting discontent in the Gulf countries, notably in Bahrain, where they have been accused of backing the Shia opposition in the country (Vakil, 2018). This chapter will seek to showcase the historical context of the relations between Iran and the GCC countries. In addition, it will give an analysis of the relations that Iran has with the different members of the GCC, particularly Saudi Arabia; and also give a sense of how these relations may evolve, taking into account current developments, like the possible restart of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) also known as, the Iran Nuclear Deal, under the new US administration of President Joe Biden and the progressive withdrawal of the US from the region.

Historical Context

The relations between the Gulf countries and Iran have always been particularly rocky, mainly due to the fact that Iran has always pursued an increase of its influence in the region and has tried to take advantage of every opportunity that it has been presented with in order to achieve this objective. This is accurately portrayed in the events leading up to the British withdrawal from the region, as Iran began to position itself on an increasingly aggressive stance towards Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, for instance even though it was unsuccessful, in 1968 Iran made a claim that Bahrain was a historical part of their country. In addition, in 1971, Iran seized the islands of Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs, which had been historically part of the UAE, and Iran continues to maintain control over these islands to this day. Moreover, Iran has also used conflicts in other countries as an excuse to increase its influence, this is what other Gulf countries have argued that Iran did during a Marxist rebellion in Oman’s Dhofar province, where Iran assisted Sultan Qaboos against the revolutionaries, and even though it has been reported that Oman saw this as a positive intervention, the rest of the Gulf countries saw it as another example of Iranian expansionism. This feeling of weariness towards Iran exponentially increased after the Iranian revolution, where the overthrowing of the Pahlavi monarchy created a sentiment of deep anxiety in the Gulf monarchies, which saw the messages that were coming from Iran as a possible cause of problems in their home countries (Vakil, 2018).

Therefore, these continuous acts by the Iranian government influenced the Gulf states into searching for methods to work together with the objective of counterweighting the Iranian influence in the Middle East. This resulted in actions like the creation of the of the GCC by the Gulf states of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in 1981, with the objective of reaching a higher level of unity among these countries, for instance through the establishment of common regulations in areas like economics, customs, commerce, education and culture, as well as the establishment of a collective security framework. This is not the only common action that the Gulf countries have taken against Iran, as they supported Iraq in the 1980–88 war (Valeri, 2015; Vakil, 2018). Nevertheless, even though the GCC was created to increase the common ground among its members, it has failed to comply with this objective several times, mainly because of the big divisions in power and influence that exist between its members, as it has been argued that this organisation is a tool used by Saudi Arabia to increase its influence among the other member states and thus, be able to move forward its agenda against competing actors in the Middle East. There are various examples, which effectively showcase these problems that the GCC has experienced, like the failed attempt at a single currency, where the Gulf Monetary Council, established in 2010 was incapable of achieving any major progress. Not only that, but another major example of failure in the work of the GCC was the blockading of Qatar by the other member states, which clearly showcased the huge divisions that exist in the organisation (Sudetic and Cafiero, 2021; Valeri, 2015). These divisions among the GCC have made it particularly difficult to achieve a common approach on major areas, which has resulted in different members having their own particular approach towards Iran (Vakil, 2018).

Relations between Iran and the GCC Members

As it has just been mentioned, the differences in agendas between the members of the GCC organisation have made it challenging to achieve a common approach towards Iran a lot of times. Nevertheless, this has also been exacerbated by the Iranian approach towards its neighbours, as it seems to lack a concrete strategy. Instead, it has been argued that the Iranian approach is widely based on opportunism, which makes it even more difficult for creating solid bridges of communication and trust between the actors involved in the region. Thus, strong bilateral relations encompassing key areas like economic relations or foreign policy have been extremely difficult to build between Gulf countries and Iran, and instead the relations between these actors are based on opportunistic moments or as a result of tensions between other players. The best example of this was the Qatar crisis of 2017, which enabled Iran to significantly improve its relations with Qatar in a mutually beneficial way. Nonetheless, Iran does not only count with a positive relationship with Qatar, as it has also been able to recently improve its relations with other members of the GCC like Oman and Kuwait, which have to balance their approach between Saudi Arabia and Iran (Vakil, 2018; Evental, 2021).

These differences have resulted in different sub-groups being created in the GCC, regarding their relationship with Iran, nonetheless, their stance are easily altered depending on the geopolitical situation, for instance since GCC countries have long enjoyed the backing of the US, as the US has operational bases in, and defence agreements with, Bahrain (home of the US Fifth Fleet), Qatar (home of the forward headquarters of US Central Command), the UAE, Kuwait and Oman. Not only that but, these countries also benefit greatly from US arms sales and even Saudi Arabia also counts with a significant degree of covert cooperation with the US. Thus, when the GCC Member States feel that the US is not fully backing them, their relations to Iran significantly soften, due to their unwillingness to provoke any escalation in tensions without US support, this was clearly showcased in 2019, when Emirati territorial waters and oil infrastructure in Saudi Arabia where attacked (presumably) by Iran and the US did not respond, so Saudi Arabia had a much more measured response. Not only that, but it has been argued that this event was also an important precursor for the start of a more diplomatic relationship between the GCC countries and Iran, as this event enabled member states of the GCC to realise that the US was not going to continue to give the same amount of importance to this region. Nevertheless, as mentioned before, there are still members of the Gulf Cooperation Council, who still believe that Iran poses a major threat. This is particularly the case for Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, for instance since 1979 both countries have referred to Iran as a military and ideological threat, as they have accused the Irani government of promoting instability among the GCC member countries. On the other hand, the other members have not adopted such a weary attitude towards Iran, this is especially the case for Qatar, which probably has the best relationship among the GCC states (Bianco, 2020).

Relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia

The relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia have never been particularly easy, as it has been widely acknowledged that the latter believes that the former is its principal threat in the region and thus, Saudi Arabia has repeatedly tried to undermine the influence that Iran is able to exert in the Middle East. On the other hand, historically Iran has argued that their actions against Saudi Arabia were only of a defensive nature, as they believed that their control in the region was only challenged by major powers like the US or Israel. Nonetheless, this changed somewhat after the Iranian revolution, as a new element of tensions entered the frame, the religious one, particularly due to the fact that the Iranian regime saw the pro-Western ties of Saudi Arabia as problematic for a country which had the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. This increase in tensions resulted in demonstrations by Iranian protesters during the annual Hajj pilgrimage, which in some cases resulted even in the death of some worshippers as the Saudi police brutally stopped these riots. These tensions continued through various years, even resulting in the break-off of diplomatic relations by Saudi Arabia in 1988, after the continuous clashes during the pilgrimages resulted in the ravaging of the Saudi embassy in Tehran (Vakil, 2018).

These continuous tensions with Iran have also severely hindered the ability of Saudi Arabia to achieve a solid common ground with the rest of the members of the GCC, particularly because in its efforts to counterweight Iranian expansionism it has tried to mobilise the GCC and get the other countries to back the Saudi anti-Iranian position, which most of the member states have viewed with weariness, as they are also troubled by Saudi influence in their countries (Vakil, 2018). Furthermore, relations between Iranians and Saudis have even worsened in recent times because of the changes in leadership that these countries have experienced. This was showcased when Prince Muhammad bin Salman rose to an influential position in Saudi Arabia, as he promoted an even stronger anti-Iranian stance, which for instance resulted in events like the execution of the Shia cleric and protest leader Nimr al-Nimr in Saudi Arabia in 2016. On the other hand, it is yet unclear how the new Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, who recently won the elections will handle these relations although some analysts have argued that he may take an even tougher stance than his predecessor President Hassan Rouhani, for instance Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, a UAE political analyst pointed out regarding the election of the new president that “Iran has now sent a clear message that they are tilting to a more radical, more conservative position.” However, he also argued that the current state of affairs in the region, makes it difficult for any player to take an even tougher stance as he argued that “nevertheless, Iran is not in a position to become more radical … because the region is becoming very difficult and very dangerous” (Ghantous, 2021; Bianco, 2020). It is unclear how the possible return to the JCPOA may affect the relations between both powers, nevertheless it may present more of a difficult question to Saudi Arabia, which sees how the new US administration under President Biden has shifted from the previous one from President Trump and may no longer provide such a solid backing to the Gulf countries, therefore, it is unclear how the Saudis can continue to stop Iranian influence from growing in the region, Jean-Marc Rickli, analyst at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy stated that “the Saudis have realised they can no longer rely on the Americans for their security … and have seen that Iran has the means to really put pressure on the kingdom through direct attacks and also with the quagmire of Yemen” (Ghantous, 2021).

Relations between Iran and the UAE

The relations that Iran and the United Arab Emirates have, is substantially different to the one that Iran has with Saudi Arabia, nevertheless, this does not mean that it is an easy one, instead it is considered a continuously changing one. This relationship has evolved in such a way due to the fact that, on the one hand, the UAE has the same concerns towards Iran than other members of the GCC like Saudi Arabia or Bahrain have. Nevertheless, Iran is not the only negative influence in the region for the UAE, as the Emirati country also sees as troublesome the Islamist axis, which has important influence in the region and is commanded by powers like Qatar and Turkey. Accordingly, the relations that the UAE has with Iran depends very much on how much power Iran has at that moment in time, especially compared with Qatar and Turkey. Recently, due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the continuous sanctions that it had been subject to, Iran was in a fragile position, quite the opposite to Turkey, which was trying to expand its influence in the region, for this reason, the UAE had been focusing their attention more on Turkey and Qatar (Bianco, 2020; Valeri, 2015).

Moreover, this relation between Iran and the UAE is smoother than with other countries like Saudi Arabia because of the fact that the UAE, unlike Saudi Arabia, does not consider Iran an internal threat, as there are no historical accounts of major dissent among the Emirati Shia population. Thus, this helps explain the changing nature of the relationship, which has gone through closer and more distanced periods, for instance in 2005 Abu Dhabi’s crown prince, Mohammed bin Zayed al-Nahyan repeatedly asked the US for strikes on Iranian targets. On the other hand, Dubai and Iran have always been able to maintain a close economic relationship, as Dubai has been a useful tool for Iran to avoid US sanctions. This resulted in a very differentiated position between Abu Dhabi and Dubai towards Iran, which was best exemplified by UAE prime minister, Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum, whose opinion of the JCPOA was much different to the one from Abu Dhabi, as he pointed out that “Iran is our neighbour, and we don’t want any problem. Lift their sanctions and everybody will benefit,” which is a very different approach than the one that Abu Dhabi had towards the Iranian Nuclear Deal, as Abu Dhabi saw it as a stepping-stone for Iranian expansion in the region. Therefore, it is very unclear how the new US administration and its change of approach towards Iran may influence the UAE and its seemingly erratic relations with Iran (Bianco, 2020; Valeri, 2015).

Relations between Iran and Qatar

It is fair to say that among all the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council, Iran has the closest relationship with Qatar. Both countries had been able to establish cordial diplomatic relations after the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), as both countries share the world’s largest natural gas field, the North Dome/South Pars, which is economically crucial for Qatar, therefore it is essential for Doha to be able to maintain the security and access to the field. Nonetheless, this closeness has been heavily influenced by how the other members of the GCC have acted against Qatar in the past, especially during the crisis of 2017, when the group known as the Anti-Terror Quartet (ATQ), composed by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt cut all diplomatic ties with Qatar, and imposed an air, land, and sea blockade. These four countries took this decision as they accused Qatar of various serious actions like supporting terrorism, maintaining excessively close relations with Iran, and interfering in the domestic affairs of its neighbours. This was crucial for moving Qatar even closer to Iran, as the Iranians offered the emirate airspace and shipping routes to avoid the blockade, this resulted in a noticeable increase in trade between both countries, between 2016 and 2017, Iranian exports to Qatar increased by 181%. Nonetheless, this has not stopped only on increased economic relations, but also on diplomatic ones, as both countries have repeatedly publicly backed each other, when there have been diplomatic tensions with other countries, as Iran has shown its strong opposition towards the action that the ATQ group has taken towards Qatar. Not only that, but Qatar also showed its opposition to Saudi Arabia by sending its ambassador back to Tehran, who had been recalled by Doha in 2016 after the Saudi execution of a prominent Shia leader, which resulted in a crisis between Iran and Saudi Arabia. This new close relationship has also prompted a change in the perception that the Qatari population has of Iran, according to a study carried out in 2018, prior to the blockade of 2017, around 30% of the country’s population saw Iran as one of the gravest threats to Qatar, however, this number plummeted after the GCC crisis started. Majed al-Ansari, professor of Political Sociology at Qatar University has pointed out that “Iran has never participated in a siege of Qatar nor participated in hostile operations [against] Qatar or Qatari interests, so it is obvious that it is not identified easily [by the Qatari public] as a national security threat [to Doha].” Nevertheless, it is still unclear how the relations between both states will continue to evolve, especially considering that there are still points of tension between both, like the fact that Qatar hosts the largest US military installation in the Middle East, the al-Udeid air base hosts 10,000 US troops, and Iran sees US intervention in the region as a major threat to their goals. However, it is possible that they maintain their closeness as it is still mutually beneficial, and even some have argued that there are still areas where they can still increase their cooperation, like on the energy sector, where Qatar has been trying to further develop its Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) industry after having withdrawn from the Saudi-dominated Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) (Sudetic and Cafiero, 2021; Cafiero and Paraskevopoulos, 2019).

Impact of the Return to the JCPOA

Recently the countries that signed the JCPOA in 2015 have been negotiating in Vienna the revival of this deal, after the US under Trump’s Presidency left. This has sparked intense controversies among the Gulf countries as some of them believe this is an inadequate deal, due to the fact that it does not cover key topics like Iran’s missile exports and support for regional proxy fighters, Abdulaziz Sager, member of the Gulf Research Center and active in past unofficial Saudi-Iran dialogue recently stated regarding the opinion of the Gulf states that “the Gulf countries have said ‘fine the U.S. can go back to (the nuclear deal), this is their decision we cannot change it, but…we need everybody to take into account regional security concerns’ (Ghantous, 2021; The Economist, 2021). Nonetheless, there are several speculations regarding how this possible revival of the deal may affect the GCC countries, some have argued that it could shift the balance of power in the region from Saudi Arabia and the UAE to Iran. This would be especially the case if the Iranian economy was able to flourish under the new circumstances, as well as, if the US continued its progressive withdrawal from the region, which would leave the Gulf countries, heavily dependent on the US for military assistance, in a very weakened position. Not only that, but this decision could also further exacerbate the already tense relations that the GCC countries have regarding their treatment of Iran. This would be especially true if the dominant power of the organisation, Saudi Arabia; demands an ever tougher position towards Iran, which countries like Qatar may not be willing to adopt. Therefore, there is a great possibility that instability in the region continues to grow, which could be disastrous, as tensions are already at a very high level. Accordingly, it is imperative that the countries involved and especially the US take the necessary steps towards securing peace in the region, especially taking into account the fact that US engagement in this region has not been as satisfactory as expected, as well as it has created noticeable opposition among the US population, which will make US action in this region increasingly unprovable, also because of the fact that it is a region with decreasing strategic importance (Parsi, 2021; Wikistrat, 2021).

US- Iran Relations

Tensions between the US and Iran have existed for over 50 years, and date back as far as 1953 where the Iranian Prime minister Mohammed Mossadeq was ousted in a coup d’état by US and British forces and the subsequent Iranian revolution in 1979. Since then, the US has traversed major incidents such as the 1971-81 US Embassy hostage crisis and the Iran-Contra scandal in 1985-86.

In 2013, the Obama-Rouhani phone call marked the first top-level conversation between US and Iranian heads of state for thirty years (BBC News, 2013) and a concentrated effort of diplomacy ultimately led to the creation of the JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action). This deal allowed Iran to increase its economic activity and bilateral relations to enter a period of relief and a “dialogue among civilisations” (Sineok and Gribanich, 2021). However, the cautious but renewed cooperation and progress made between them proved short-lived as the Trump administration tested new limits.

Indeed, Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy which included withdrawal of the JCPOA nuclear deal in May 2018 and increased economic sanctions on Iran has only served to escalate tensions and distrust between the two nations. It also led to the reversal of non-proliferation gains as Iran abandoned its voluntary implementation of the Additional Protocol to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

Iran’s economy suffered significantly as the Trump administration pressured other states to cut Iranian imports of oil, its primary export which represented 20% of the OPEC country’s GDP (World Bank, 2021). Oil exports reportedly dropped from 2.5 million barrels per day to a few hundred thousand in 2020, which also had to be sold at a discounted price as global oil prices fell during the pandemic (Fitzpatrick, 2020). Despite this however, Iran’s full compliance with the deal for a year after the US withdrawal (Arms Control Association, 2021), arguably showed a willingness to restore the nuclear deal.

Nevertheless, the effects of sanctions on the Iranian economy, whereby crucial government revenues from oil and gas exports were severely reduced, has been cited by Iran as a key factor in their diminished capacity to effectively respond to the pandemic (Reuters, 2020). Another source of tension was the Trump administration’s blocking of an emergency IMF loan, with Iran calling the move “medical terrorism” and a “violation of international medical conventions” (Al Jazeera, 2020).

However, the height of recent tensions was the US targeted killing of Gen Qasem Soleimani in January 2020 by US drone strike in Iraq, which saw Iran vowing “severe revenge” (BBC News, 2020b). This provoked Iran to declare it would also no longer abide by any previous commitments or obligations made within the nuclear deal. Indeed, since then Iran has progressively infringed on JCPOA conditions by, inter alia, continuing to test advanced centrifuges and amassing enriched uranium (Marcus, 2020; The Economist, 2021). Yet they have asserted they will continue to work with the UN’s nuclear monitor, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Biden has promised to re-join the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran and announced softer policy plans. However, academics and policy makers agree a return to the JCPOA is easier said than done. With the announcement of Ebrahim Raisi as the winner of the Iranian presidency on the 18th June, there have been some concerns that the reinstating of the JCPOA may prove more difficult under Raisi than Rouhani, who viewed the deal as a cornerstone of their administration (Barzani, 2021). Indeed, reduced cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency has been pointed out as a potential risk.

Nevertheless, at their first press conference on 21st June Raisi spoke in favour of reviving the nuclear deal (BBC News, 2021b). Yet, Raisi stated that even if the JCPOA is restored, he would not meet directly with Biden (Barzani, 2021; BBC News, 2021b), supporting the early view that the process would require a parallel regional dialogue and that bilateral negotiations are for now at least, off the table.

Nuclear talks had resumed in Vienna in April with Iran, the remaining P5+1 parties and US envoys engaging indirectly and based in another hotel across the street (BBC News, 2021). Talks were adjourned on the 20th of June (Irish and Hafezi, 2021) and progress has been slow with Iran demanding all economic sanctions imposed by the US be lifted before it ensures compliance. The EU Envoy leading the talks to reinstate the JCPOA said on June 30th that there is a “new level of optimism” but the E3 have aired caution, praising the recent progress but highlighting “success was not guaranteed” (Murphy and Irish, 2021).

Yet, in the last few days an IAEA announcement confirmed that Iran has started the process of enriching uranium up to 20% U-235[1], an amount alarmingly closer to weapons grade to which US and EU officials have declared would complicate or ultimately sink indirect negotiations with the US (Murphy et al, 2021). Indeed, The US announced this signified an “unfortunate step backwards” (Murph et al, 2021) and a joint statement by British, French and German ministers highlighted how this move is “threatening a successful outcome of the Vienna talks” and expressed “grave concern” (BBC News, 2021).

The prospect of Iran acquiring nuclear weapons has been highlighted as a severe threat to both regional and global security and having negative repercussions on attempts to prevent the spread and proliferation of further nuclear weapons (Meier, 2013). Whilst academics have highlighted the slim likelihood of a clandestine Iranian nuclear operation, considering the Israeli penetration of the programme, others have pointed out that the recent departure of Trump and Netanyahu may bolster a more confident Iran (Barzani, 2021).

Challenges & Reflections

US-Iran relations have faced a volatile relationship for years, but they have been especially strained during and as a product of the Trump administration. Their troubled relationship has been exacerbated by changing administrations and powerful rhetoric on both sides, a lack of diplomatic relations, and repeated US military interventions in the region (Atlantic Council, n.d.). Indeed, re-establishing trust will be challenging and indeed some have highlighted mistrust of US intentions as the largest obstacle to JCPOA negotiations (Eqbali, 2021).

What’s more, whilst the US wants Iran to fully return to its commitments under the JCPOA before taking any actions, Iran insists since the US unilaterally withdrew from the deal, they should lift sanctions first (Eqbali, 2021). Thus, there is a risk of reaching an impasse where neither party wishes to take the first step.

The “sanctions wall” was also imposed by the Trump administration with the express purpose of making a return to the JCPOA more difficult (Ghaffari, 2021). Indeed, if Iran insists on a rolling back of all sanctions under Trump’s campaign, Biden faces both logistical and political obstacles as it will take both time and political will-power to dismantle. Additionally, not all sanctions are in violation of the JCPOA. For instance, some individuals or entities may have been targeted due to their involvement in cyber attacks on US infrastructure (Riley, 2019). Thus, navigating the lifting of sanctions will be challenging.

Yet, whilst there remain clear challenges, there is a consensus of hope in reviving the nuclear deal (International Crisis Group, 2021). Whilst outright normalisation of relations between the states is unlikely, cooperation on limited matters has been suggested as a means to rebuild mutual trust (Hussain et al, 2021). It is acknowledged however that since the JCPOA has dominated conversations, other discussions surrounding, inter alia, human rights and development have become securitised. Yet, by removing a major source of tension between the two states, state officials have highlighted that a return to the JCPOA would represent an opportunity to commence new discussions with Iran and neighbouring states to address regional security issues such as the conflict in Yemen and Syria (Parsi, 2021).

Academics have also highlighted Iran’s desire to be better integrated into the international community to benefit from global economic integration and resolve the current economic crisis it faces (Hussain et al, 2021), which could perhaps be a future point of negotiations.The US also holds the power to facilitate the $5 billion IMF emergency loan which Iran has requested to help fight coronavirus. Indeed, Iran remains one of the countries worst hit by the virus with over 80,000 deaths.

Lastly, a staggered approach where individual steps are adopted in parallel has been suggested as the best route to both nuclear and regional de-escalation to mitigate the risk of an impasse (International Crisis Group, 2021).

[1] U-235 is the most suitable isotope for nuclear fission. 20% constitutes high enriched uranium but can be used in medical applications and research. 90% enriched uranium constitutes weapons grade uranium (BBC News, 2021).U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan

The Twin Towers attacks on the United States made Afghanistan an important foreign policy concern of the US and started a military campaign against the Al-Qaeda and the Taliban government. During the period of about more than eighteen years, the US has lost 2,400 military personnel in Afghanistan as of April 30, 2020. The US has also spent $137 billion for the process of reconstruction in Afghanistan (Tariq, Rizwan, Ahmad, 2020). Former US President Trump and Joe Biden announced, this year (2021), his country’s decision regarding the final and unconditional withdrawal of US military forces from Afghanistan, stressing that this process should be completed on the anniversary of the September 11 attacks (Ullah Bahadur, 2021). The withdrawal ends the longest war the US has ever fought, 20 years after it began in 2001. This will have great impact on the security paradigm of the regional as well global politics, since the main focus of the world rested upon the counter-terrorism strategy and strengthening security system. Yet the departure of foreign troops does not signify an end to Afghanistan’s conflict, now largely dependent on intra-national dynamics. The Biden administration, with the realization that U.S. military presence is not the answer to achieving lasting peace in Afghanistan, has decided to make a clean break with previous strategy by implementing a non-conditions-based withdrawal deadline. It is precisely at the national and regional levels, and more particularly on the peace negotiations, governance and security, terrorism, regional dynamics, great power competition, human rights, humanitarian issues, and development, that this withdrawal will have a considerable impact. Now, the main concern of the US and its coalition partners is to bring political stability and peace in Afghanistan and around after they leave the country within a specific time frame.

The American presence ensured relative stability in the Gulf region, deterring Taliban terrorist actions and keeping ISIS at bay. Foreign actions were rare, as the slightest mistake could have repercussions on a major international level. But now there is nothing to stop terrorist groups from attacking a weakened Afghan state, devoid of its funds, nor foreign states from acting in the open in this fragile area. This part will therefore focus on providing an analysis of the national and regional impacts that this precipitous withdrawal of the United States could have, with a particular focus on the role of Iran in this matter.

Context and prospects for the peace agreement

After more than a year of negotiations, U.S. and Taliban representatives signed a bilateral agreement on February 29, 2020, agreeing to two “interconnected” guarantees: the withdrawal of all U.S. and international forces by May 2021, and unspecified Taliban action to prevent other groups, including Al Qaeda, from using Afghan soil to threaten the United States and its allies (Thomas, 2021). In the months following the agreement, the United States pointed out that the Taliban was not holding up its end of the bargain, particularly with regard to Al-Qaeda (Reuters, 2020). For example, in its report on the final quarter of 2020, the Office of the Inspector General for the Department of Defense relayed an assessment from the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) that the Taliban maintain ties to Al Qaeda and that some AQ members are “integrated into the Taliban’s forces and command structure” (Operation Freedom’s Sentinel). U.S. officials also described increased Taliban violence as “not consistent” with the agreement (TOLO News, 2020). Although no provisions in the publicly available agreement address Taliban attacks on U.S. or Afghan forces, the Taliban reportedly committed not to attack U.S. forces in non-public annexes accompanying the accord.

Joe Biden’s decision to withdraw troops is reminiscent of Barack Obama’s decision in 2011 to withdraw US troops from Iraq. However, we are reminded of the disastrous repercussions this may have had for the country, notably the meteoric rise of ISIS and the gradual plunge of Iraq into chaos (Khalilzad, 2016). The withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan comes at a very difficult time, as the Afghanistan-peace process faces successive pitfalls, as well as violence in the country is escalating significantly, which means that the country may be exposed to several future dangers, at a time when the United States of America no longer has a desire to bear the burdens of the security presence in Afghanistan, in light of its changing political and strategic priorities. Acts of violence have increased in the country, as some reports estimated terrorist attacks in various provinces of Afghanistan during the first three months of 2021 at about 60 attacks, especially with the stalled peace process Afghani, between the internationally recognized government and the “Taliban” movement (Bahadur, ibid).

According to the agreement, the Taliban will “not allow any of its members, other individuals or groups, including al-Qaeda to use the soil of Afghanistan to threaten the security of the United States and its allies,” (USDS, 2020) but they have failed to break ties with al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups. Although the Taliban have technically participated in the Intra-Afghan Negotiations, their sincerity in reaching a political compromise with the Afghan government remains unclear. In part, Biden’s decision is a conditions-based response to the Taliban’s failed compliance with the agreement’s conditions. However, America’s new deadline is absolute, and withdrawal appears to be no longer contingent on the Taliban’s adherence to conditions outlined in the U.S-Taliban Agreement.

Intra-Afghan Negotiations

Intra-Afghan negotiations began in September 2020 with the goals of establishing a comprehensive peace settlement among Afghans. Major negotiating issues include reducing violence and establishing a future governance structure for the Afghan state (Thomas, ibid). Although the Afghan government has once again reiterated its commitment to making an end to the fighting and the security of its people a top priority, it is not clear that this is the case, the Taliban remain determined to secure an agreement on the structure of the Afghan state before any ceasefire discussions begin (Putz, 2020). The Biden administration has insisted that it will put “full weight” into diplomatic efforts to reach a peace agreement between the Afghan government and the Taliban. However, it cannot be said that this sustained diplomatic effort has been a success, as it has not produced any results. Furthermore, the Taliban are currently refusing to participate in any negotiations until the withdrawal of foreign forces is complete (Shalizi, 2021). This negotiation process, if it is to show anything, is the domination of the Taliban, which, moreover, is not the only one, and therefore have demonstrated little interest in the compromise or power-sharing, for which American negotiators have pressed. In a recent speech, the Taliban’s deputy leader, Sirajuddin Haqqani stated that “No mujahid ever thought that one day we would face such an improved state, or that we will crush the arrogance of the rebellious emperors and force them to admit their defeat at our hands. Fortunately, today, we and you are experiencing better circumstances” (Nossitier, 2021). The most likely scenario in the future is that the Taliban will gradually gain the upper hand in the negotiations, without ever reaching a compromise with the Afghan state, which would result in the continuation of this “eternal war”.

The withdrawal of foreign troops and other sources of assistance will weaken the Afghan government and undermine capabilities of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) in countering Taliban influence, resulting in a loss of potential influence and legitimacy (Dobbins, Cambell, Mann, Miller, 2019). A weakened Afghan government will embolden the Taliban and increase the risk of state collapse. The U.S.-led NATO advisory mission has improved the technological capabilities of the ANDSF but hasn’t fully weaned its dependency on international advisors for critical support and sustainment functions. A withdrawal of foreign troops would give the Taliban a slight military advantage over the ANDSF. The presence of U.S. and NATO coalition forces has prevented the Taliban from gaining control of Afghanistan’s largest cities, Kabul and Kandahar. After withdrawal, these cities are more likely to fall to the Taliban.

One of the risks hanging over the withdrawal of American troops is therefore the rise in power of the Taliban, which could lead to the emergence of a new regional terrorist organisation in the long term. A non-conditions-based U.S. withdrawal is likely to empower terrorist and extremist groups who see U.S. withdrawal as a clear sign of victory. Without crucial human intelligence, surveillance and direct-action capabilities, the U.S. may lose the ability to closely monitor expansionist activity by various terror groups in Afghanistan. An emboldened al-Qaeda or the Islamic State may be able to reconstitute, posing significant risks to Afghan civilians, neighboring countries, and the West (Mir, 2020).

The relative stability western troops have been able to bring to Afghanistan has caused significant collective action problems regarding development and counterterrorism assistance. Afghanistan’s neighbors will be forced to fill security gaps left by the withdrawal of US and NATO forces. Furthermore, Afghanistan’s geo-strategic location serves as a division of power between China, Iran, Russia, India, and Pakistan. In the international coalition’s absence, Afghanistan could become a playing field for great power rivalries (Brenner & Wallin, 2021).

The days after: Peace or Chaos?

Afghan officials have sought to downplay the detrimental impact of the U.S. troop withdrawal while emphasizing the need for continued U.S. financial assistance to Afghan forces (Rahimi, 2021). U.S. military officials have said various options, including remote training (which has largely been in place since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic) or training Afghan personnel in third countries, are under consideration to continue supporting Afghan forces. Beyond the immediate effects on Afghan forces and their capabilities, a full U.S. military withdrawal may have second-or third-order effects on the fragile Afghan state, especially when it comes to local perceptions of U.S. intentions and of the impact of U.S. withdrawal on Afghan forces. Some Afghans, recalling the complex, multi-sided civil war of the 1990s, have suggested that their communities may pursue more independent courses of action if the Afghan government is unable to provide security in the context of the U.S withdrawal (Engel Rasmusse & Amiri, 2020).

Operations led by the Taliban, whose strength has been estimated at 60,000 full-time fighters, against Afghan government forces continue, including numerous attacks nationwide after the U.S. withdrawal began on May 1. A major offensive by the Taliban in May 2021 prompted the United States to launch airstrikes in support of Afghan government forces in southern Afghanistan’s Helmand Province. The group controls or contexts more territory in 2021 than at any point since 2001 by many measures (UNSC, 2021). In recent years, about 50 percent of the Afghan state budget and 90 percent of its military and police costs have been borne by international donors. Reductions in such funding will have a direct impact on the capacity of the government and the combat capabilities of its armed forces. Governance structures in Afghanistan consist of overlapping layers of formal, centralized de jure authorities; regional power bro-kers with mixed official and informal authority; and varied de facto mechanisms for organizing and regulating social behaviour at the local level (Dobbins et al., ibid). This will deprive the central government of this capacity and disrupt the equilibrium of central versus regional power that has settled into place since the U.S. intervention. In addition to the decline of the central government, the Afghan economy will also decline. In Kabul, the technocrats will staff the ministries in much the same way as they have for the past decade, but policies, military orders, and money will likely reach a far smaller part of the country than they have in the past.

The Taliban will consolidate its hold on the rural, Pashtun-dominated south and east; continue its current aggressive push into the non–majority-Pashtun north and west of the country; and begin concerted efforts to take and hold urban areas, particularly provincial capitals. U.S. air support, including American forward air controllers on the ground, has been critical in denying the Taliban control of major population centers (ibid). The growing strength of former president Hamid Karzai and his allies, which may include the Kandahar security apparatus of the recently assassinated Abdul Raziq, could make the southeast and its gateway to Kabul a more contested area than the Taliban anticipates. On the other hand, the splitting of Tajik and Uzbek communities by recent infighting and by the Taliban may mean that the north and west are significantly more contested than in the past. Thus, the future map of political control may not precisely resemble the ethnic map (ibid). In the aftermath of the troop withdrawal, Kabul will not be the only city to be contested. In such a multi-sided conflict, the fighting will become more urban than rural, more stand-and-fight than hit-and-run, and more reliant on heavy weaponry likely to cause civilian deaths and major damage to basic infrastructure, much of it financed by the United States.

The Taliban seized the key district of Panjwai, in their former stronghold of Kandahar province, on Sunday 4 July, after night-time fighting against Afghan forces. The Taliban’s latest capture comes as the full withdrawal of US troops approaches. The capture of Panjwai by the Taliban came two days after the departure of US and NATO troops from Bagram, their largest base in Afghanistan, located 50 kilometres north of Kabul and the hub of coalition operations against the Taliban for the past 20 years (Le Monde, 2021). “The Taliban seized the police headquarters in the district and the governorate building” after a night of fighting, the governor of Panjwai district, told Hasti Mohammad. The chairman of the Kandahar provincial council, Jan Khakriwal, confirmed the fall of Panjwai, while accusing Afghan forces “in sufficient numbers” of “intentionally withdrawing” (ibid). Fighting has been raging for weeks in several Afghan provinces and the Taliban claim to control around 100 of the country’s nearly 400 districts.

Total international withdrawal from Afghanistan will likely be followed by a reduction in foreign assistance and subsequent civil war, further deteriorating an already dire humanitarian situation and undermining development progress. Afghanistan has the second largest refugee population in the world, and four million people are internally displaced (Brenner & Wallin, ibid). A total withdrawal of troops and a halt to funding can only lead, even in the short term, to an increase in this devastating humanitarian crisis. Mounting violence has escalated Afghanistan’s brain drain as the country’s young and educated seek safer futures abroad. 2021 has seen a campaign of assassinations in Kabul targeting journalists, civil servants, judges, and activists (Smith & Mengli, 2021). Cuts in donor support to Afghanistan have already begun. As the U.S. further decreases its security and economic assistance to Afghanistan, other countries are unlikely to fill funding gaps (Brenner & Wallin, ibid).

Regional influence of the withdrawal

Regional powers and the involvement of the international community are very important to the conflict in Afghanistan. With NATO forces out of the way, India and Pakistan may intensify their competition for influence in Afghanistan. Both countries have significant stakes in Afghanistan, as its stabilization is integral to regional security in South Asia. India is the largest regional contributor of development assistance to Afghanistan and aims to cultivate relations with the country as a natural gas partner and ally against Pakistani Islamic militants (Grishin & Nasratullah, 2020). Pakistan is largely focused on undermining India’s influence in Afghanistan and growing the influence of the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI), Pakistan’s national intelligence agency which has known links to the Taliban’s Haqqani network (Chaudhuri, et Shende, 2020). According to the US officials, the terrorists have their sanctuaries in Pakistan but that charge has been rebutted by Pakistan saying that the Taliban have increased their influence in Afghanistan and hence has strengthened their territorial control over some areas (Clayton, 2018). Instability in Afghanistan would have a great impact on the security paradigm of Pakistan, which has been struggling hard against the militants and insurgents on its own for long and has conducted many military operations against the insurgents with the last one as Operation Zarb-e-Azabthat brought about fruitful results to Pakistan (Tariq, 2018). Relations between the two countries have already deteriorated with the many Afghan migrants on Pakistani soil. Pakistan’s security establishment, fearful of strategic encirclement by India, apparently continues to view the Afghan Taliban as a relatively friendly and reliably anti-India element in Afghanistan. India’s diplomatic and commercial presence in Afghanistan and U.S. rhetorical support for it exacerbates Pakistani fears of encirclement. The role of Pakistan is very central to the process of peace and stability in Afghanistan, which fact is also admitted by the US and allied forces. Without the support of Pakistan, it is very difficult to facilitate negotiations either between the US and Taliban or between the Taliban and Afghan government (Tariq, 2020).

Afghanistan may also develop cordial relations with China owing to the growing popularity of China in Asia and at the global level. China’s priority concern in Afghanistan is the spillover of insecurity and radicalization. Specifically, Beijing remains concerned that Afghanistan will become a haven for Uyghur separatists and threaten stability in the Xinjiang province. In 2018, China assisted the Afghan military with the construction of a mountain brigade in the north. In 2019, China built a military base for its own use in Tajikistan near the Wakhan Corridor, a strategic route connecting Afghanistan to China (Azad, 2021). It is therefore likely that China will continue to strengthen the Afghan defence infrastructure in order to halt the advance of the Taliban, which it does not want to see in power. As Afghanistan’s largest foreign economic investor, Beijing’s economic opportunity in the country relies thus heavily on peace and security. China already has land use contracts with Afghanistan and is waiting for the complete withdrawal of the US to implement them. There are also plans to include the country in the new Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the massive and priority objective of Chinese government concerning Foreign Affairs. So if peace is to be negotiated, it will be with China.

Financial support for the Taliban also comes from Russia. The main justification, also mobilised by Iran, is to fight against the Islamic State by preferring the Taliban, fighting evil with a lesser evil in short. Secondarily, Moscow aims to actively fight against U.S. interests in a type of zero-sum strategy. Russia views Afghanistan as an arena of competition with the West and will likely expand its geopolitical interests in the region once U.S. and NATO forces make a complete withdrawal (ibid). Since Intra-Afghan negotiations began Moscow has maintained relations with a variety of stakeholders to ensure a leading role in any post-conflict political settlement. Building a cooperative relationship with the Taliban and other political parties will ensure that Moscow’s interests are secured in a post-U.S. Afghanistan (ibid).

Iran’s growing support for the Taliban

During the past years financial and material support to the Talibans have been observed partly from Iran. Throughout the Intra-Afghan peace process Tehran has adopted the policy of “strategic hedging” to protect its interests in Afghanistan. Of course, Iran is not totally aligned with the Taliban, either religiously or in terms of demands, and it is more of a strategic partnership. Simultaneously, Tehran won support from Afghanistan’s Tajik and Hazara populations. By maintaining good relations with both the Afghan government and Taliban, Iran has prepared itself for a variety of outcomes (Brenner & Wallin, ibid). Iran also intends to put an end to the outbreaks of violence on the border between the two countries. With international forces gone, Iran will likely intervene more heavily in Afghan affairs, the United States no longer acts as a thorn in its side.

However, Iran and Afghanistan have had historical and cultural relations and share multiple ties. Approximately 20% of the population of Afghanistan is Shia including the Hazaras, and Iran considers itself as the “Guardian of Shia’s across the globe” (Barzegar, 2014). Afghanistan shares its 936 kilometers of western borders with Iran, crossing through rivers and deserts. Provinces of Farah, Herat, and Nimruz are linked with Iran. Taliban established their government in Afghanistan in 1996, and Iran considered this government of the Taliban as a threat to the stability of Iran and its influence in the South and Central Asian region. But in Afghanistan, the control of the Taliban with the help of Pakistan and Saudi Arabia was the real worry for Iran. The Eastern province of Iran has a large community of Sunni Muslims. Sunni Muslims in the eastern province of Iran named Baluchistan were opposing Shia theocracy. Taliban also supported those insurgents in Iran (Boone & Dehghan, 2016).

In the first instance, Iran and America both wanted a centralized government in Afghanistan that would stop the revival of the Taliban in the country. Iran had closed ties with Northern Alliance leaders, who did not want to share power with Hamid Karzai in the government. But Iran used her influence on Northern leaders to sit with Karzai in the government anyway (Worden, 2018). The end of the Taliban regime provided Iran an opportunity to build its relations with her neighbor and enhance her influence in Afghanistan. Iran is hosting Taliban leaders and militants of Hizb e Islami but on the other hand, Iran is also providing financial aid to the Afghan government (Ahmed & Junai, 2020). Sectarian differences create troubles between both sides. Afghanistan has a Sunni majority while Iran has Shia Muslims in large numbers. Afghanistan is the only country in the region that shares Islamo-Persian identity with Iran, which only sees Afghanistan as a state intervened by Super Powers and its serious effects on it. Soviets invaded Afghanistan and approximately 1.5 million refugees fled towards Iran. While the American invasion put up thousands of soldiers in front of Iran (Kugelman, 2018). Following the end of the Taliban regime, Iran has invested massively in Afghanistan and economic ties between Iran and Afghanistan have become stronger. Different companies in Iran are working in Afghanistan on different projects: Iran’s main focus is to construct roads to connect both countries. Afghanistan is not connected directly with the sea route, and Iran and India want to decrease Afghanistan’s dependency on Pakistan. For this purpose, Iran is going to work on road projects to connect Afghanistan with Chabhar port (Farooq, 2019). Iran has planned a rail track from Herat to Mashhad which will support the economy of Afghanistan, Herat being considered as the most developed and well-managed city of Afghanistan due to the cooperation of Iran. There is no doubt that Iran has invested a handsome amount and has a political, social, and economic interest in Afghanistan. Iran rejected the peace deal between America and the Taliban saying that America has no legal position to deal with the Taliban. Initially, Iran thought that this peace deal only an attempt to provide legitimacy to America in Afghanistan, but Biden’s statement about the total withdrawal by September has changed the game.

Now Iran has four non-negotiable political, economic, security and strategic interests in Afghanistan (Verma, 2021). First of all, Iran wants to set up a government in Afghanistan that is favorable to it, in order to create a Shia sphere of influence stretching from the Middle East into Central Asia via Afghanistan. This is to counter the spread of Wahabi/Sunni Islam propagated by Saudi Arabia, UAE and Pakistan (Ghattas, 2020) and also to increase its influence in Central Asia (Akbarzadeh, 2015). Iran has always wanted to maintain a regional security policy, to maintain a robust and active political security presence in its neighbourhood to forestall future security problems and it continues to do so through Afghanistan. It is to this end that Tehran wants an inclusive and pluralistic national unity government in Kabul favorable towards Iran (Barzegar, ibid). Instability in Afghanistan will lead to a rise in terrorism and extremism in the region and beyond as witnessed in the past, and the re-emergence of the Taliban. Iran is aware that Afghanistan became a terrorism hub when the Taliban were in power from 1996–2001. Therefore, it does not want a Taliban led or dominated government in Kabul or the establishment of an Islamic Emirate by the Taliban. It is apprehensive that an Islamic Emirate or Sunni/Wahabi Afghanistan will become a launchpad for anti-Iran activities (Kutty, 2014). So it seems that Iran is once again playing a fuzzy double game in the country to strengthen its regional position.

Secondly, Afghanistan is considered as the central point of the Iran’s ‘Look to the East’ grand strategy. This strategy aims to establish close energy and economic ties with countries in East Asia and South Asia especially China, Japan and India, and Iran plans to use Afghanistan as a conduit for supplying oil and gas to China, India and other countries (Verma, ibid). This policy will also aid Iran in stabilizing Central Asia and South Asia especially Afghanistan through economic integration: a stable Afghanistan is absolutely necessary to achieve these goals. Iran also seeks a favorable transit route to Europe and Central Asia. It wants to be an indispensable partner in regional integration and to increase its economic influence in the region and beyond, and also develop and diversify its economy (Kutty, ibid). Iran also intends to preserve the investments it has made in the west of the country, which we described above concerning the city of Herat and access to the sea. To protect its economic interests, Iran has resisted development initiatives in Afghanistan that are outside the context/ambit of Iran-Afghanistan relations. For instance, the Tajikistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India pipeline and network of roads and railways linking India with Central Asia via Iran (Kutty, ibid). These economic developments will increase Iran’s material resources and the will for Iran to become a great regional power in its legendary quest for Islamic leadership to counter Saudi Arabia.