Genocide is perceived as the ‘crime of all crimes’ and the worst form of violence amongst humans (Rafter, 2016; 1). Yet, despite its recognition as a tragedy, policymakers are yet to fully acknowledge the relationship between human and national security and thus recognise genocide as a threat in the same way it recognises other threats (Gallagher, 2013).

Security as a Concept

Security is subjective and the significance of the concept has various meanings inherent to different contexts, disciplines and environments, but generally revolves around the idea of threats (Purpura, 2010). Thus, security is understood in terms of the referent object to which it pertains (Williams, 2013). Traditional understandings of security pertain to national security and are state-centric (Bilgin, 2008). As such, this idea is often dominated by realist theorists who refer to the anarchic system in which states exist, and threats to state security existing in the form of external threats, primarily from other states. Attinà (2016), details the scope of such threats which can include dangers to state values, territorial integrity or political sovereignty.

Non-traditional security on the other hand, refers to less conventional issues that have emerged as the area expanded, particularly after the Cold War, including both threats to national and human security (Collins, 2016). Human security, was first articulated as a concept in the 1994 United Nations Human Development Report (UNDP, 1994), which is of particular importance as it not only pioneered the idea that security could be about people instead of territories, it also introduced the contestable nature of security as a concept that has now become particularly evident in security related literature (Persaud, 2016). This report proposed several fundamental areas of human security including economic, environmental, community, food, health, personal and political security (UNDP, 1994). Human dignity was also included later as an important value to be protected (Persaud, 2016).

Genocide Defined

The term genocide was officially institutionalised in article II of the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Here it was identified as the ‘intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group’ through killing, mental harm, prevention of births, forcibly transferring children or the deliberate inflicting conditions calculated to bring physical destruction in whole or in part (OHCHR, 2019; para 7). Yet despite this, it remains one of the ‘most controversial and contested terms in international relations’ (Baker 2018; 233), as academics often deliberate over the difficulty of determining intent, the types of groups that should be included (such as if political groups should also be incorporated), what acts constitute ‘destroying’, and disputes over if a community must be destroyed ‘in whole’ or ‘in part’ (Baker, 2018).

- The Threat to Human Life

The most fundamental security issue genocide poses is the clear threat to human life and personal security with an estimated 50 million people having died from genocide in the 20th century alone (Lindert and Prierbe, 2006). Whilst realists would argue states only have moral obligations to protect their own citizens and that this is therefore not regarded as a traditional security threat, it could be argued that genocide does in fact pose a traditional security issue in the sense that it also threatens some of the most essential values of the state such as the right to life and human dignity (Hiebert, 2015). Further, as highlighted later it has consequences that can indirectly endanger national security.

Additionally, millions further remain at risk from the effects of exposure such as mental illness (Lindert and Prierbe, 2006). Mental trauma and illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression are significantly elevated as a result of witnessing or experiencing such atrocities from genocide and thus pose a threat to health under the remit of human security.

Yet analysing genocide from a gendered perspective, there are also particular human security issues that disproportionately effect women within the context of genocide. For instance, whilst historically rape has been viewed as a product of conflict, it has now been increasingly recognised that mass rape is used as a tool to degrade, demoralise, dehumanise and traumatise female victims in cases of genocide as part of military policy, leading to the coining of the term ‘genocidal rape’ (Bartrop and Totten, 2007). This has been evident during the Bosnian Genocide of the 1990s, the Rwandan Genocide of 1994 and the ongoing Rohingya Genocide just to name a few. In the case of Bosnia this was often used as a method of forced impregnation in ‘rape camps’ by Serbs (Staveteig, 2011). In some cases, Bosniak women were imprisoned until sufficient foetal development meant they could no longer safely access an abortion (Bartrop and Totten 2007; Staveteig, 2011). This has strong immediate and long-term effects on human security and the mental health of female victims as a result. Additionally, it can often lead to the limited social and interpersonal functioning of many victims (Lončar et al, 2006), thus it can be seen how it has the potential to also impact economic security, as they face an additional barrier to successfully entering the workforce, something especially problematic when numerous family members are likely to have perished.

Genocidal rape also has particular ramifications for Bosniak muslims, as it is not only likely to lead to the creation of pariahs, but women are often resultantly perceived as tainted religiously, as female chastity is an essential component related to family honour (Bartrop and Totten, 2007; Snyder et al, 2006). Yet the scale of this occurrence is difficult to determine with true accuracy as stigma associated with reporting such crimes means many instances go underreported (Snyder et al, 2006). Nevertheless, it can be seen that human security is regularly affected in cases of genocidal rape both in the short and long-term.

Additionally, in the case of Rwanda, physical health security has also been threatened by the transmission of HIV/AIDS through genocidal rape. Amongst many others throughout the time of the genocide, Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, the first woman to be convicted of genocidal rape, incited militia to carry out mass rape against Tutsi women (Sperling, 2006). Amongst the estimated 250,000- 500,000 raped, roughly one in four contracted HIV/AIDS as a result, many of whom died from not receiving treatment in time (Bhalla, 2019). Thus, from a feminist perspective, genocide has the potential to disproportionately affect many facets of female human security as it poses a threat to personal and health security and human dignity.

2) The Threat of Migration

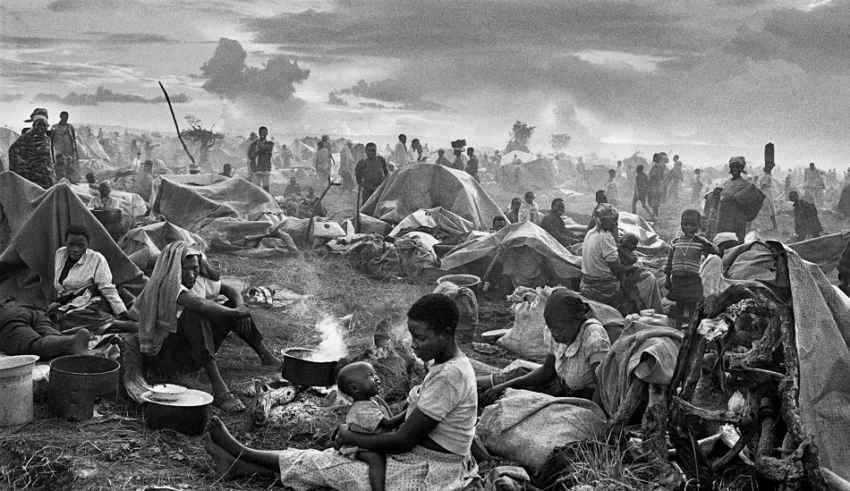

Leading on from this, genocide therefore further promotes instability, especially in already weak and undemocratic states (Hiebert, 2015). These often have spill-over effects with global and transboundary effects (Albright and Cohen, 2008). For example, genocide creates vast numbers of refugees and displaced persons both within and outside of state borders. The Holocaust and the Bosnian Genocide have both produced the largest number of displaced persons in Europe (Young, 2001).

Thus, the destabilisation of whole regions and increase in irregular migration as a result of genocide, can also be viewed as a traditional security threat to the state as it arguably diminishes their territorial integrity and therefore may also undermine notions of state sovereignty, as those fleeing conflict often cross borders without official authorisation (Koser, 2011). For instance, the transboundary effects of the Rohingya genocide and its implications for traditional state security can be illustrated through the influx of refugees into neighbouring countries such as Bangladesh. Such displacement can also have particularly negative security implications for Bangladesh, a state which already suffers from extreme overpopulation.

Additionally, out of the estimated 418,000 Rohingyas living in Bangladesh only 30,225 are officially registered, thus the majority of Rohingyas in Bangladesh are classified as illegal (Bashar, 2012). This also has non-traditional security implications to the state for Bangladesh in terms of crime. In the case of the Rohingya, with many unable to seek legal employment due to their illegal status, they become involved in transnational criminal activities such as the drug trafficking of narcotics (Bashar, 2012). Additionally, Rohingya refugees have been blamed for an increase in violence such as the 2012 Ramu Tragedy in Cox’s Bazar directed at Buddhists where shrines and monasteries were destroyed (Rachana, 2018).

Whilst the securitisation of migration is not a new phenomenon or unique to genocide, it has been increasingly perceived as a threat to national security in more recent years due in part, some have argued, to the increased scale of international migration and threat of illegal migrants (Koser, 2011). Thus, in this sense, genocide can indirectly increase securitisation discourse regarding migration. Yet what is also notable, is the increases in such migration securitisation narratives that have also had other security implications, simply through classifying it as such. Some argue that the securitisation of migration has effectively justified certain more extreme measures and restrictive migration and refugee policies (Koser, 2011). For instance, outright deportation or offshore detention centres where asylum seekers often spend many years to get processed pose severe threats to human security in terms of mental and physical health, and economic security, as asylum seekers are often denied employment privileges within centres (von Werthern et al, 2018). Additionally, the securitisation of migration, particularly amongst refugees has facilitated the existence of xenophobic ideologies (Moreno, 2019). Indeed, such xenophobia is arguably what provided the necessary conditions for genocide in Myanmar in the first place, since Rohingya Muslims were initially perceived as illegal immigrants which lead to their extreme marginalisation and ultimately genocide (Siddiqui, 2018).

(3) The Threat of Terrorism and Militarised Groups

Additionally, there have been increasing concerns that the influx of refugees into other states may be a breeding ground for potential terrorism as radical and militant extremists may pose as refugees to enter target states (Özbek, 2018). Yet, there have been severe disputes regarding whether or to what extent terrorists genuinely or successfully exploit such refugee channels (Moreno, 2019). There is, however, more consensus that legitimate refugees are more vulnerable to religious radicalisation due to their complex legal status and socio-economic hardship which make them capable of being militarised (Moreno, 2019). This is a threat to both human security and international security and can endanger both origin and host countries. For instance, the Rohingya genocide has been blamed in part for the increase of Jihadi terrorist groupings both in host countries of Rohingya refugees and Myanmar (O Wolf 2017).

Moreover, in the long-term, return-migration may also pose a security threat to the nation state they are returning to. As noted by Lischer (2011; 263), whilst the negative impact of refugee return migration is often framed in terms of ‘absorptive capacity’, what is often ignored is the real threat of returnees that include fighters or individuals who are mobilised upon return. This has been highlighted as a security threat to both individual and national security as it has the potential to undermine the entire peace process. For example, in Rwanda, despite most refugees simply wishing to return to build a peaceful life, the repatriation of militarised Tutsi refugees has been highlighted as a significant security issue that has received insufficient attention due to the severe risks it poses (Lischer, 2011; Mamdani, 2001).

4) The Threat to National and Individual Economic Security

Genocide can also have severe implications for the economic security of the nation state as it can aggravate pre-existing demographic challenges that further exacerbate these issues. For example, Bosnia’s population pre-genocide, having undergone a demographic transition to below replacement fertility, was ageing and showing little sign of improvement (Staveteig, 2011). However, mass emigration of Bosnians due to the 1990s genocide and ethnic cleansing was especially evident amongst economically active and mobile populations and limited return migration has occurred since, due to existing tensions and political instability that remains (Intézet, 2018). Thus, as a result, Bosnia’s population is increasingly shrinking, with total fertility rates below lowest-low (consistently below 1.3), and dependency ratios increasing as further people leave, which signifies a greater burden to the economy to provide social services and tackle widening inequalities.

This presents a negative feedback loop where economic development is hindered due to the lack of working-age populations, institutions lack financial capabilities to recover leading to economic stagnation and unemployment which causes further economically active Bosnians to leave and making return migration less attractive. Bosnia currently now has some of the highest youth unemployment globally, with 47.4 percent of youth unemployed (World Bank, 2019) which clearly has consequences for individual and state economic security. Yet such economic insecurity can also be viewed as a more traditional security threat. Without economic security, the strong financial foundations needed to maintain military deterrents for potential external threats, central to traditional understanding of security, are also compromised (Neu and Wolf, 1994).

5) The Threat of Infectious Disease

In a globalized environment, infectious disease has also been recognised as a transboundary threat to both national and human security (Lo Yuk Ping and Thomas, 2010), a threat that is facilitated by the mass migration evident in genocidal settings. This security issue can be evidenced through the 1997 Cholera outbreak amongst the 90,000 Rwandan refugees who fled to The Democratic Republic of the Congo (D.R.C, formerly known as Zaire) (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 1998). In such contexts of genocide, displaced persons who flee the conflict often end up in refugee camps where there is poor sanitation, water quality and hygiene practices often combined with severe overcrowding, all of which seek to exacerbate the potential for disease (Connolly et al, 2004). Within one refugee camp alone in the D.R.C. the cholera outbreak affected 48,000 individuals and caused 23,800 deaths (WHO, 2019).

This is also a national security issue for the D.R.C as it impedes its ability to develop and has the potential to effect pre-existing social and economic structures (WHO, 2019). For instance, it not only puts strain on the economy in terms of medical costs of treatment, it can indirectly affect productivity and commerce (Cecchine and Moore, 2006), its ability to trade with other countries, and destroy huge tourism industries thus diminishing a country’s ability to tackle such security issues. For instance, due to imposed food trade embargos and negative impacts on the tourism industries, the 1991 Cholera outbreak in Peru cost the country US$770 million (WHO, 2019).

(6) Security Issues Associated with Recognition and Labelling Genocide in the Long-Term: The ‘g-word’

The recognition or lack thereof regarding the term ‘genocide’ can also be regarded as a particularly noteworthy response to an indirect security issue. For instance, the avoidance of using the term genocide in the context of the Armenian genocide 1915-1917, might appear superficially as an ideological decision but others dispute this. Zarifian (2013) argues that US officials who omit classifying a conflict that meets the characteristics of genocide, like in the Armenian case, do so primarily due to ‘geopolitics and economics’ (Zarifian, 2013; 83). In other words, this is arguably a security strategy to allow them to maintain relations with Turkey and keep them as an ally, and by default maintain a traditional understanding of security with reference to the state. This is partly evidenced through the promotion of formal recognition of the Armenian Genocide from Barack Obama from his position as a senator and the omission of the term ‘genocide’ when in office. This was particularly evident in the statements made on the Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day on April 24th 2014, where Obama avoided the term, instead calling it a ‘Meds Yeghern’ which translates from Armenian to mean ‘Great Crime’. Other US officials have also contended that that such labels were only of significant relevance to historians but not politicians (Zarifian, 2013).

Yet on the other hand, non-recognition of genocide also poses a non-traditional security issue insomuch as it drives beliefs that the United States are almost engaging with Turkish denialism and therefore support or endorse it (Zarifian, 2013). This poses a threat to the human security of Armenians in the U.S, where there is a large diaspora. For instance, denialism has been found to perpetuate victims’ psychological impacts, encourage further victimisation and have detrimental effects to their identity (Alayarian, 2008). As put by Parent (2016; 44), ‘it recreates the conditions under which the victims’ extreme suffering is perpetuated and further victimization is made possible, yet again.’ This also often has intergenerational effects whereby ideologies of hatred are passed on through generations (Campbell, 2001). Moreover, it can set the stage for future conflict and suffering as war narratives and misinformation spread and facilitate the recurrence of violence (Tolbert, 2015; Campbell, 2001). Thus, it can be seen how both the recognition and non-recognition of events of genocide have negative security implications which serve to highlight just how contentious and divisive the concept of genocide is.

(7) The Threat of Intervention: R2P and The Genocide Convention

Leading on from this point, the recognition of genocide when it is taking place, is particularly contentious also due to the forming of the Genocide Convention of 1948 and more recently the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine in 2005, a global commitment which calls for measures of various forms of intervention such as mediation, economic, sanctions and military involvement, in the face of, inter alia, genocide and atrocity crimes (Viikari, 2015). Although the R2P framework is non-binding, it is still grounded in international law and expected to be observed. Additionally, the Genocide Convention highlights the obligation to undertake measures to prevent and prosecute acts of genocide, and many have now been deemed as norms under the remit of customary law, which binds states regardless of whether they are party to the convention (UN OSAPG, 2019). Thus, there is a consequent debate that follows surrounding when the term genocide is triggered, if legal obligations automatically ensue (Kelly, 2007). Labelling a conflict as ‘genocide’ in many views does in fact oblige states to intervene through some measure and potentially risk their own security, particularly if they have deployable military units (Kelly, 2007). As a result, genocide may instead be referred to as ‘civil war’ or ‘ethnic conflict’ to relieve themselves of such obligations that could commit them to the use of their own resources endangering their own economic and military security (Campbell, 2001).

Again, using the example of the United States, under the Clinton Administration and during the Rwandan genocide, U.S officials were directed to avoid the term ‘genocide’ despite senior officials’ agreement that it constituted as such (Jehl, 1994). This therefore highlights that due to preservation of state security it is not in their national interest to do so. Thus, what may once have been viewed as a failure of the American political system to intervene in instances of genocide, is now increasingly perceived by some scholars as one that is in fact ‘ruthlessly effective’ in supporting its own inaction (Power, 2003; xxi).

Indeed, this security issue is not unique to the Armenian genocide, in the case of the Rohingya Muslims in the Rakhine State, there is also a lexical issue and the term genocide has been actively avoided as a security strategy for certain states (Lee and Ducci, 2018). Certain academics have argued that this could be due to the powerful international partners that support Myanmar, including most notably China (Lee and Ducci, 2018). This falls under what Hiebert (2015) calls the ‘Goldilocks problem’. Put simply, non-intervention, according to Hiebert, can be explained by ‘Non-Goldilocks’ instances of conflict or genocide that occur in areas that are perceived to western states as either of limited strategic value or ‘hyper strategic value such that intervention is considered to be too dangerous a proposition’ (Hiebert 2015; 13). In this instance, Myanmar constitutes a location of ‘hyper’ strategic value in Southeast Asia and thus states may seek to actively avoid using the term genocide to avert any real or perceived threats to their state security. Thus, as argued by Kelly (2007), states wish to have the choice of acting but wish to evade any explicit requirement affirming that they must do so.

However, illustrated through the Bosnia vs. Serbia case, the International Court of Justice held the Serbian government accountable for the Srebrenica genocide of 1995 in Bosnia-Herzegovina, despite their refusal to label the violence as genocide, as they had the means to prevent genocide but manifestly refrained from employing them (ICJ, 2007; 194). Moreover, the uncertainty surrounding whether the Rohingya crisis could be considered genocide was alleviated somewhat through the official accusations of genocide by The Gambia against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice. However, an official ruling of genocide may take years to establish, whilst violence continues.

(8) The Threat to Sovereignty

Lastly, abiding by the R2P doctrine may also have security implications for traditional principles of non-intervention in domestic affairs and Westphalian notions of sovereignty which emphasise complete autonomy and sovereignty over a state’s citizens. Under this idea, international security is reliant on the principles that proscribe intervention in another state’s domestic affairs (Bellamy, 2016). Thus, under this framework, international security may be threatened by humanitarian intervention and it may justify potential future violations of sovereignty in the future. Indeed, the NATO ‘humanitarian war’ launched in Kosovo in 1999 to prevent further genocide and ethnic cleansing without UN authorization sets a dangerous precedent that threatens the normative foundations of the world order (Thakur, 2002). For example, as put by Thakur (2002; 325) such actions not only violate international law but in doing so ‘undermine world order based on the centrality of the UN as the custodian of world conscience and the Security Council as the guardian of world peace’. This could therefore serve as a direct threat to traditional understandings of security as it could encourage the misuse of force or sufficiently authorise a state’s ability to violate other states’ sovereignty and therefore threaten the latter’s national security. Whilst Campbell (2001) believes, rather optimistically this does not present a security issue as abuse of power will ultimately face some form of accountability when the global community become aware of such deception, other scholars have highlighted the potential naïvety of such philosophies (Hintjens, 2003).

Yet, almost paradoxically, without such intervention in instances of genocide, this arguably also threatens traditional understandings of security. As highlighted by Campbell (2001; 16), inaction also threatens the liberal international order and ‘left unchecked’ genocide has the potential to ‘destroy whatever security, democracy and prosperity exists in the present international system’. Thus, what we see is through the R2P and the Genocide Convention is essentially a trade-off between national and human security.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article has distinguished between traditional and non-traditional security in an attempt to show how the concept of security has broadened over time. It has also highlighted the far-reaching direct, non-direct, short and long-term security issues associated with genocide. Indeed, genocide has a significant impact on security at a number of different levels from the individual, to the nation state and international community. These include the threat to human life, the threat of recognition, intervention and sovereignty, the threat of migration and associated threats of terrorism, transfer of disease and economic instability. All of these have consequences and often unforeseen externalities for all forms of security due to the complex and sometimes tenuous interrelationship between them. Moreover, through the securitisation of these issues, there is often a trade-off, whereby national security is prioritised over individual or human security. Policy makers must take note of this and incorporate a broader understanding of security to develop more effective security policy in the future.

References

Albright. M., Cohen. W., (2008), Preventing genocide: A blueprint for U.S. policymakers. Washington: The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, The American Academy of Diplomacy, The Genocide Prevention Task Force.

Attinà, F. (2016) Traditional Security Issues, In Wang, J. and Song, W. (Eds.) China, the European Union, and the International Politics of Global Governance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Baker. A., (2018), Genocide, In Brown W., McLean I. and McMillan A. (Eds.) Concise Dictionary of Politics and International Relations, Oxford University Press.

Bartrop, P.R. and Totten, S., (2007) Dictionary of Genocide [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO.

Bashar, I. (2012) New Challenges for Bangladesh. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 4(11), pp. 10–13.

Bhalla. N., (2019), How mass rape in genocide transformed Rwanda’s response to AIDS, Reuters,

Thomson Reuters Foundation [online], Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-rwanda-genocide-aids-feature/how-mass-rape-in-genocide-transformed-rwandas-response-to-aids-idUSKCN1RN00C, Accessed: 28/09/21

Bilgin. P., (2008), Critical Theory, in Security Studies an Introduction (eds Paul Williams), 1, pp. 89-116. Routledge.

Campbell. K., (2001), Genocide and the global village, Springer.

Cecchine. G., Moore. M., (2006), Infectious Disease and National Security, Strategic Information Needs, RAND National Defense Research Institute, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica.

Collins, A., (2016), Contemporary security studies, Oxford University Press.

Connolly. M. A., Gayer. M., Ryan. M. J., Salama. P., Spiegel. P., and Heymann. D. L. (2004) Communicable diseases in complex emergencies: impact and challenges, Lancet, 364(9449), pp.1974–1983.

Gallagher. A., (2013), The Impact of Genocide on International Order. In: Genocide and its Threat to Contemporary International Order. New Security Challenges Series. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Hiebert. M.S., (2015), Genocide Prevention and Western National Security: The Limitations of Making R2P All About Us. Politics and Governance, 3(4), pp.12-25.

Hintjens. H., (2003), Review of Genocide and the Global Village. African Affairs 102(406), pp. 164–166.

International Court of Justice (ICJ)., (2007), Case Concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro), Judgement [online], Available at: https://www.icj-cij.org/files/case-related/91/091-20070226-JUD-01-00-EN.pdf, Accessed: 27/08/21

Intézet. M., (2018), Turbulence in the Balkans, Again: Bosnia and Herzegovina and its Current Migration Crisis, Migration Research Institute.

Jehl, D., (1994), Officials Told to Avoid Calling Rwanda Killings ‘Genocide’. The New York Times.

Koser, K. (2001), When is Migration a Security Issue? Brookings, [online], Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/when-is-migration-a-security-issue/, Accessed: 30/08/21

Lee. P. K., Ducci. C., (2018), Why No Humanitarian Intervention in the Rohingya Crisis? A Political Alignment Between the West and China, European Consortium for Political Research, [online], Available at: https://ecpr.eu/Events/PaperDetails.aspx?PaperID=38937&EventID=115, Accessed:31/08/2021

Lindert, J., and Priebe, S. (2006) Long-Term Health Impact of Genocide and Organized Violence. Epidemiology 17(6): S119.

Lischer. K., (2011), Civil war, genocide and political order in Rwanda: security implications of refugee return, Conflict, Security & Development, 11:3, pp. 261-284.

Lo Yuk-ping, C., and Thomas, N. (2010) How is health a security issue? Politics, responses and issues. Health Policy and Planning 25(6), pp.447–453.

Lončar, M., Medved, V., Jovanović, N., and Hotujac, L. (2006) Psychological Consequences of Rape on Women in 1991-1995 War in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Croatian medical journal 47(1), pp. 67–75.

Mamdani, M., (2001), When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism and the Genocide in Rwanda, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report., (1998), Cholera Outbreak among Rwandan Refugees —Democratic Republic of Congo, April 1997, Report, 47 (19), pp. 389–391.

Neu, C. R., and Wolf, C. (1994) The Economic Dimensions of National Security: Product Page, RAND Corporation, National Defense Research Division, Santa Monica.

OHCHR., (2019), Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, [online], Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crimeofgenocide.aspx, Accessed: 01/12/21

Özbek, N. (2018) Refugees as scapegoat for terrorism. Journal of Human Sciences 15(4), pp. 1968–1978.

Parent. G., (2016), Genocide Denial: Perpetuating Victimization and the Cycle of Violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal, 10 (2).

Persaud. R., (2016), Human Security, (eds Collins A.) in Contemporary Security Studies, 4, pp. 139-153, Oxford University Press.

Power. S., (2003), ‘A problem from Hell’. America and the age of genocide, Perennial, An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, New York.

Rafter, N. (2016) What Kind of a Crime Is Genocide?: Capsule Summaries of Eight Genocides. In The Crime of All Crimes. NYU Press.

Siddiqui. H., (2018), Can we stop xenophobia that led to genocide of the Rohingya?, The Stateless Rohingya, [online], Available at: https://www.thestateless.com/2018/12/can-we-stop-xenophobiathat-led-to-genocide-of-the-rohingya.html, Accessed: 26/08/21

Snyder. C., Gabbard. W., May, J., & Zulcic. N., (2006), On the Battleground of Women’s Bodies: Mass Rape in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Affilia, 21(2), pp. 184–195.

Sperling, C. (2006) MOTHER OF ATROCITIES: PAULINE NYIRAMASUHUKO’S ROLE IN THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE. Fordham Urban Law Journal 33(2), pp. 637.

Staveteig. S., (2011), Genocide, Nuptiality, and Fertility in Rwanda and Bosnia-Herzegovina, UC Berkeley, eScholarship.

Thakur, R., (2002) Outlook: intervention, sovereignty and the responsibility to protect: experiences from ICISS. Security Dialogue, 33(3), pp.323-340.

Tolbert. D., (2015), The Armenian Genocide: 100 Years of Denial (And Why It’s In Turkey’s Interest to End It), International Center for Transitional Justice.

UNDP (1994), United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report1994, New York: Oxford University Press.

Viikari. L. (2015) Responsibility to Protect and the Environmental Considerations: A Fundamental Mismatch or the Way Forward? The Responsibility to Protect (R2P), pp. 348–404.

Von Werthern, M., Robjant, K., Chui, Z., Schon, R., Ottisova, L., Mason, C., and Katona, C. (2018), The impact of immigration detention on mental health: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 18(1): 382.

WHO (2019), Global epidemics and impact of cholera, [online], Available at: https://www.who.int/topics/cholera/impact/en/., Accessed: 25/08/21

Wolf. D. S. O., (2017), Genocide, exodus and exploitation for jihad: the urgent need to address the Rohingya crisis: 42. World Bank (2019), Unemployment, youth total (% of total labor force ages 15-24) (modeled ILO estimate), The World Bank Group, [online], Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.1524.ZS, Accessed: 01/09/21

Zarifian. J., (2013), The United States and the (Non-) Recognition of the Armenian Genocide, Études arméniennes contemporaines, (1), pp.75-95.

By The European Institute for International Law and International Relations.