On December 15, 2022, Dominic Ongwen was sentenced by the Appeal Chamber (AC) of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to 25 years of life in prison for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda, movement of which he was a senior commander (1). Ongwen’s case is unique in that the ICC found itself to deal with an offender that purposefully and deliberately caused great anguish to his victims. However, this same perpetrator is an individual who had previously gone through great suffering provoked by the same organization who abducted him as a young boy and by which he eventually served as one of its leaders. Ongwen’s past as a child soldier divided prosecution and defense on what to do about the determination of his guilt and a debate over the victim-perpetrator logic emerged in the courtroom. This notwithstanding, any individual who is responsible for illicit acts must be brought to justice, independently of their position (2).

The LRA has been committing atrocities in Uganda and neighboring countries for more than 35 years. Today, it is a low-intensity conflict as the group’s agenda is significantly different from LRA’s original intent, which was to overthrow Museveni’s government (Uganda’s President) and create a Kingdom based on the Ten Commandments (3). Levels of violence spiked over the years and brutalities have been committed by both the LRA and the government’s army. However, ICC’s judicial procedures have, to date, investigated only the crimes committed by the rebel group in that the matter was referred to the Court by Museveni (4), therefore, since the indictment, the ICC has failed to be impartial in its action. After the issuance of arrest warrants in 2005, out of five LRA’s wanted senior leaders, Dominic Ongwen is the only individual that has appeared before the Court’s judges. Three other suspected perpetrators of heinous crimes are dead (or presumed so) and LRA’s top commander, Joseph Kony, has never been captured: today, assumed that he is alive, is at large (5). Ongwen appeared at The Hague exactly 15 years after the issuance of his arrest warrant (6); this is due to the difficulty in capturing perpetrator as well as for the lengthy of judicial procedures that often characterize ICC’s work.

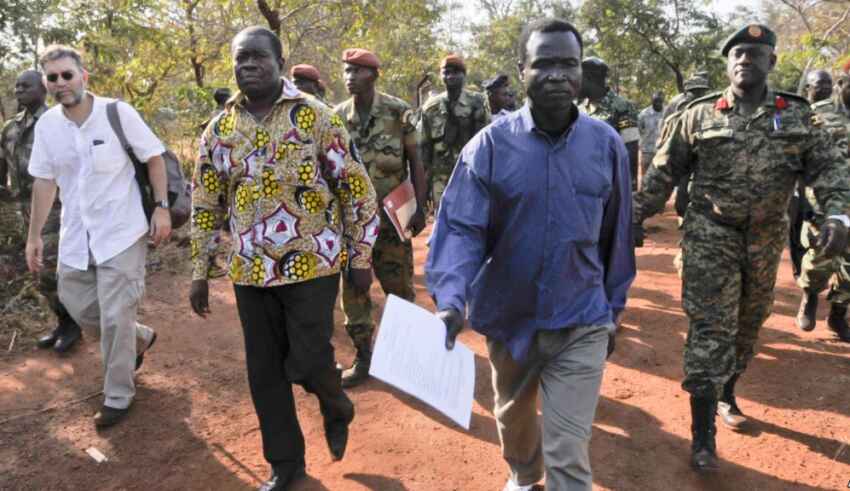

The image of Ongwen as a perpetrator but at the same time of a victim of the heinousness performed by the rebel movement of which he was a member was what his defense team leveraged during the trial. Ongwen’s early capture and spiritual education, according to his defenders, prevented him from integrating into civilian society and its principles, which is why he never attained mental maturity. Moreover, the defense relied on the fact that even when the accused began to develop critical reasoning skills, he did not escape from the LRA because of the fear instilled in him from the earliest days of his abduction about the consequences that such action would entail: his killing and that of his family. However, as highlighted by the prosecution, Ongwen is not the same as other children abducted and forced to kill against their will. In fact, he mimicked his oppressors with great vigor and for that he rose in LRA’s hierarchy. This does not diminish the fact that Ongwen was once a victim, nevertheless he is not an exceptional and outstanding example: as a matter of facts, there were thousands of other young, abducted boys and girls who, out of fear of consequences, forgot about civilian life and dedicated themselves to the LRA’s cause in order to survive, becoming then ferocious perpetrators. This notwithstanding, Ongwen’s case came before the ICC as he rose the hierarchy of the rebel movement and became one of its most uninhibited commanders (7). It has to be presumed that at the time of the perpetration of brutal acts, Ongwen was an individual with rational reasoning capabilities, hence he knew he was committing wrongful acts. Ongwen was found guilty of 61 crimes comprising crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in northern Uganda between July 1, 2002 (date from which the ICC has jurisdiction in examining the crimes committed by individuals under trial in that it is the date in which the Rome Statute, ICC’s establishing treaty, entered into force) and December 31, 2005. The ICC claimed Ongwen’s full responsibility for such acts: after psychiatric evaluations, the Court convened that there was no evidence in support of the assumption that he may had suffered of mental illness or disorder giving his history of fighting with the LRA nor that Ongwen committed such brutal acts under coercion (8).

Ongwen’s conviction was decided considering the individual as a criminal responsible for brutal acts regardless of his past as a child soldier. As stated, Ongwen was aware of the seriousness of the acts he was committing on behalf of the LRA and he consciously decided to rise in the group’s hierarchy, becoming one of the most vicious commanders. In the view concerning that no perpetrator of atrocities should remain unpunished, the prosecution has well demonstrated the facts supporting the need to try and convict Dominic Ongwen. The sentence is to be seen as fair in that it punishes the perpetrator, but at the same time allows Ongwen the chance to build a civilian life subsequently to having served his sentence. It will be necessary to monitor how his reintegration into the community to which, for most of his life, has caused serious damage both physically and psychologically, will happen.

References:

By The European Institute for International Law and International Relations.