Within a few months, the European Court for Human Rights found Turkey accountable twice for violating Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights concerning the freedom of expression. In April 2021, in the case of Ahmet Hüsrev Altan v. Turkey, the Court held that there had been an infringement of the applicant’s freedom of expression and freedom of the press, and there was no reasonable suspicion for his detention. In October of the same year, ECtHR, in the landmark decision Vedat Şorli v. Turkey, not only found that there was a violation of Mr. Şorli’s right of expression but also that Article 299 of the Criminal Code, which provides a higher level of protection to the President of the Republic than the other people, interferes with Article 10, urging the government to bring the domestic law in line with the Convention.

In complete contrast with ECtHR’s decisions and following the broad crackdown on media in Turkey, the parliament in October 2022 passed the new “disinformation law” that accords up to three years imprisonment to anyone for disseminating misleading information. The law includes 40 articles amending, among others, the Internet law, the Penal Code, and the Press Law. However, the most debatable and concerning is Article 29. The provision designates it an offense with prison sentences of up to three years to publish “false information” with the intent to “instigate fear or panic” or “endanger the country’s security, public order, and general health of society.”

This new legislation builds on an Internet law passed in 2020, according to which big social media platforms have to put in charge a local representative and remove from their websites any offending content within two days period. The disinformation law sets a four-hour time limit for the companies to remove such posts following a court order or as decided by Turkey’s Information and Communication Technologies Authority (ICTA). In addition, under the new legislation, the tech companies are obliged to hand over to the ICTA any information that the agency may request. In case such platforms fail to comply with any removal request, content blocking, or order to report any data the law introduces severe sanctioning.

Another alarming objective of the new disinformation legislation is the extension of the application of the Press Law to online news sites. The provision includes cancelling news posts that violate media ethics and compliance with obligations to run corrections on the front page for a week if the website is ordered to do so. Under the veil of the country’s security and public order, the Turkish government uses severe fines to control social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook, applying pressure on tech companies to abuse the user’s rights. The vague wording of the law adds further concerns over its implementation. The legislation lacks to define crucial terminologies like “disinformation” and “disturbance to public peace”, triggering questions on the determination of responsibility and guilt.

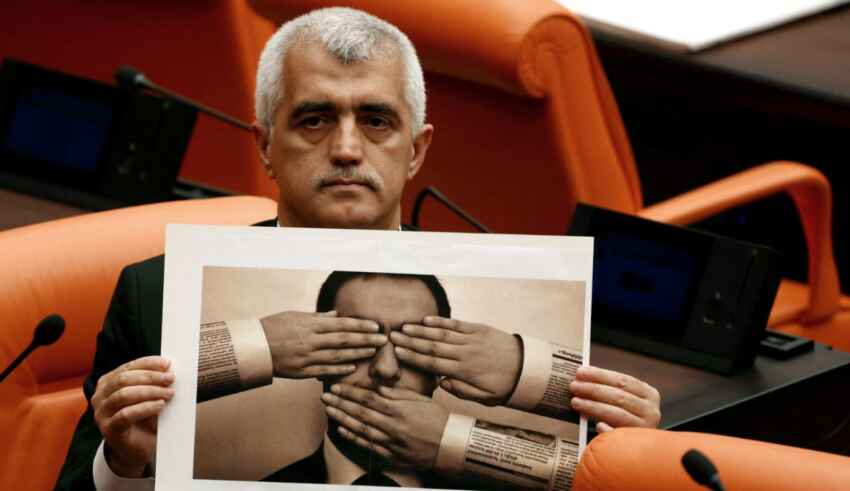

The timing of the new law is not surprising, as it comes a few months before the 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections in Turkey. In response to the severe criticism that the Turkish government is subject to, the disinformation law is an added weapon in its arsenal to control media and enforce censorship. That is how the vagueness of the legislation favors the Turkish government. The widely drawn provisions allow the politically-controlled courts to interpret the law according to the government’s interests and censor any criticism against it.

By The European Institute for International Law and International Relations.